‘But why has the rum gone ?’

- Captain

Jack Sparrow; Pirates of the Carribean

On July 31, 1970, Britain’s Royal Navy issued its last daily rum ration and with it, the rum soaked history

of pirates and sailors finally succumbed to the modern-day sobriety. The iconic and much revelled relationship of sailors and rum (initially

called ‘Kill Devil’, a raw white spirit runoff from the sugar refining process)

is an intriguing tale of the compulsions of landlubbers and the hard life at

sea and predictably it all started in the Caribbean. In the 17th

century unable to sell the large amounts of rum, the sugar cane farmers got

into contracts with the Royal Navy for supply of the spirit to ships. A

symbiotic relationship, there started a timeless tradition of rum and the

sailor. Even today the tradition of gifting a spirit originates from this

association where a good deed was rewarded with an extra pint of rum.

However,

rum was not the original spirit (it was beer) nor it was the only thing on the

sailor’s plate in the Nelsonian Navy of 1700’s. Many a day at sea, the Royal

Navy had evolved an elaborate system of ration entitlements comprising of a

number of items including a wine gallon of beer (approximately 3.78 litres) per

day. In fact, the ration scale was first set up in 1677 and was published as

part of Royal Navy regulations in 1733.The scale looked something like this[1]:-

ITEM/DAY

|

Biscuit

|

Beer

|

Beef

|

Pork

|

Pease

|

Oatmeal

|

Butter

|

Cheese

|

Pounds Avoirdupois

|

Gallons wine measure

|

Pounds Avoirdupois

|

Pounds Avoirdupois

|

Pint Winchester Measure

|

Pint Winchester Measure

|

Ounces

|

Ounces

|

|

Present day equivalence

|

453.59g

|

3.785 L

|

453.59g

|

453.59g

|

500 gms

|

500 gms

|

25 gms

|

25 gms

|

Sunday

|

1

|

1

|

1

|

½

|

||||

Monday

|

1

|

1

|

1

|

2

|

4

|

|||

Tuesday

|

1

|

1

|

2

|

|||||

Wednesday

|

1

|

1

|

½

|

1

|

2

|

4

|

||

Thursday

|

1

|

1

|

1

|

½

|

||||

Friday

|

1

|

1

|

½

|

1

|

2

|

4

|

||

Saturday

|

1

|

1

|

2

|

|||||

Total

|

7

|

7

|

4

|

2

|

2

|

3

|

6

|

12

|

This

basic ration scale actually lasted till about 1847 (from 1677) when the

Admirality finally accepted the technology of canning. Of course, to suggest

that the meals were locked on to this scale would be to exaggerate and

predictably there were substitutes available for pursers to buy depending upon

availability.

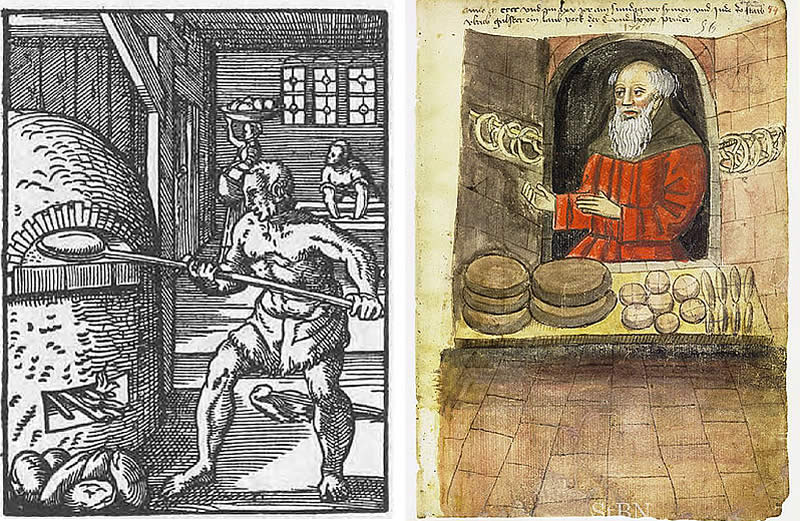

The

most obvious question which begets from the basic ration scale is the idea of

preservation which, as one would infer, was limited to natural methods like

baking, salting, pickling and drying and therefore by long tradition, the

seaman’s diet was based on salt meat, dried pease or beans and articles made

from cereals. As one author has commented, “what the sailors ate at sea was

what landsmen ate during the winter”. For example, biscuits (which included

bread also, when referred to as soft loaf) was preferred by the Royal

Victualling board since it could last much longer, came in handy sizes and was

comparatively (to bread) easier to make. Of course, this biscuit was not really

‘ready to bite’ and required some breaking and soaking before eating. Similarly,

the popularity of rum was purely because it lasted much longer than its other

cousin, beer, not to mention it’s more spirited performance otherwise.

The

most obvious question which begets from the basic ration scale is the idea of

preservation which, as one would infer, was limited to natural methods like

baking, salting, pickling and drying and therefore by long tradition, the

seaman’s diet was based on salt meat, dried pease or beans and articles made

from cereals. As one author has commented, “what the sailors ate at sea was

what landsmen ate during the winter”. For example, biscuits (which included

bread also, when referred to as soft loaf) was preferred by the Royal

Victualling board since it could last much longer, came in handy sizes and was

comparatively (to bread) easier to make. Of course, this biscuit was not really

‘ready to bite’ and required some breaking and soaking before eating. Similarly,

the popularity of rum was purely because it lasted much longer than its other

cousin, beer, not to mention it’s more spirited performance otherwise.

How It Got There ?

The

ration scale though fascinating to read about did not mean that the food and

drink appear on the ships by magic. It was all organised under the Victualling

Board which reported to the Admirality Board and operated through a system of

contracts much like the present-day system. Elaborate systems of supply,

inspection and delivery evolved over time with eventual segregation of supply

and delivery. Also, while contractors were supplying bulk of the items, the

manufacturing yards of the Victualling board were slaughtering and packing

meat, baking biscuits and also brewing beer and manufacturing casks as well. In

fact, almost half the tradesmen working in the manufacturing yards were

involved in the making of casks which was considered very important for quality

control purposes. Similarly, in the year of 1797, for about 110,000 men at sea, approximately

23,000 bullocks and 115,000 pigs passed through altars of the yards. The meat

was packed and shipped off but there are interesting disposal stories of what

was left behind not to mention that dumping of left overs in the estuarine

waters resulting in extra fattened crabs and oysters. The system of stocking

and supplying ships was a primitive cousin to the present one. The person of

interest here was the head of the Victualing yard called the ‘Agent Victualler’ who used to draw a

handsome salary and was not just responsible for the running of yard and

stocking of ships but also to provide ships pursers with adequate currency to

buy provisions at foreign ports and islands. He was also responsible to provide

the ships with vegetables, fresh meat and tobacco. As one would understand by

now, the paper work was elaborate and time consuming.

The

ration scale though fascinating to read about did not mean that the food and

drink appear on the ships by magic. It was all organised under the Victualling

Board which reported to the Admirality Board and operated through a system of

contracts much like the present-day system. Elaborate systems of supply,

inspection and delivery evolved over time with eventual segregation of supply

and delivery. Also, while contractors were supplying bulk of the items, the

manufacturing yards of the Victualling board were slaughtering and packing

meat, baking biscuits and also brewing beer and manufacturing casks as well. In

fact, almost half the tradesmen working in the manufacturing yards were

involved in the making of casks which was considered very important for quality

control purposes. Similarly, in the year of 1797, for about 110,000 men at sea, approximately

23,000 bullocks and 115,000 pigs passed through altars of the yards. The meat

was packed and shipped off but there are interesting disposal stories of what

was left behind not to mention that dumping of left overs in the estuarine

waters resulting in extra fattened crabs and oysters. The system of stocking

and supplying ships was a primitive cousin to the present one. The person of

interest here was the head of the Victualing yard called the ‘Agent Victualler’ who used to draw a

handsome salary and was not just responsible for the running of yard and

stocking of ships but also to provide ships pursers with adequate currency to

buy provisions at foreign ports and islands. He was also responsible to provide

the ships with vegetables, fresh meat and tobacco. As one would understand by

now, the paper work was elaborate and time consuming.

The

RN tryst with the rations and spirits

is an account which is replete with anecdotes and trivia which every sea farer

can relate to. Of course, the RN

though a benchmark of sorts is not the only Navy which was operating at that

time and the systems of other Navies would also throw up interesting tales of

victual management in the time when refrigeration or canning were not

available. It also lends us the historic perspective of our modern-day practices.

Military history overwhelmingly has been an account of wars and battles with

Sun Tzu and Clausewitz being celebrated the world over but there is interesting

trivia and lessons buried the logistical challenges faced when war was a

frequent occurrence and technology had much catching up to do.

Much

of the present post is based on the book ‘Feeding Nelson’s Navy’ by Janet

McDonald detailing the various aspects of Victualling management onboard and

ashore. Another, land mark book on logistics is the seminal work of Dr Martin

Crevald called ‘Supplying War : From Wallenstein to Patton’ which is probably

the most comprehensive work covering Logistics challenges from the 30 years war

till the WW-II campaigns. Both the books are interesting reads for logisticians

across the world for many lessons, anecdotes and to probably to answer the

question; “But why has the rum gone?”